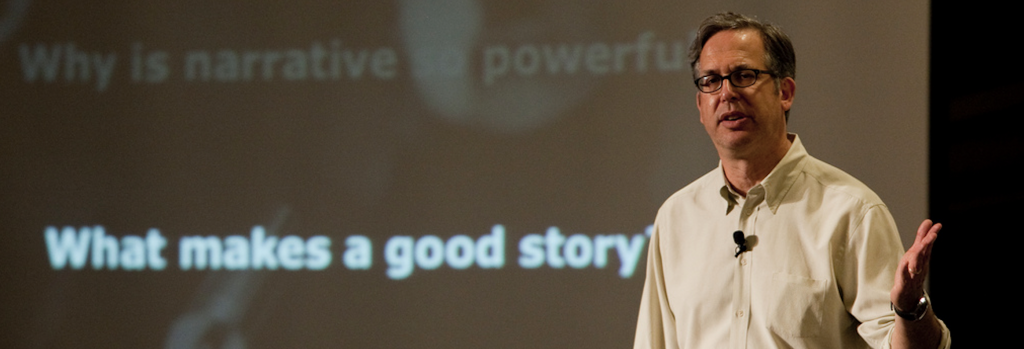

When I began this work in 1998, gas was $1.07 per gallon. The world’s most popular mobile phone was made by Nokia. The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation did not exist. Also absent from the public interest sector was significant interest in the craft of storytelling. Whenever I would talk to prospective clients about improving their narrative skills, reactions ranged from disinterest to mild disdain. Get serious, many told me. One doesn’t change the world with a bunch of anecdotes.

Twenty-four years later, I can report that attitudes have changed dramatically. It’s hard to find a public interest organization today that isn’t telling stories or talking about ways to “change the narrative.” That said, I cannot report that all the stories I’m seeing are well-told or are the best kinds of stories to tell. Even more troubling are the stories told in ways that do more harm than good. So, for this month’s edition of free-range thinking – the last I’ll author – I have five requests for those who still aspire to tell truly world-changing stories.

Twenty-four years later, I can report that attitudes have changed dramatically. It’s hard to find a public interest organization today that isn’t telling stories or talking about ways to “change the narrative.” That said, I cannot report that all the stories I’m seeing are well-told or are the best kinds of stories to tell. Even more troubling are the stories told in ways that do more harm than good. So, for this month’s edition of free-range thinking – the last I’ll author – I have five requests for those who still aspire to tell truly world-changing stories.

First, be clear on the kinds of stories you’re telling and what you expect them to accomplish. In the public interest sector, most stories tend to fall into one of two categories: journalistic stories or dramatic narrative.

Journalistic stories are designed to provide everything the audience needs to know within the first few paragraphs, answering the essential who, what, when, where, why and how questions that define “news.” The remaining paragraphs fill in the story’s details in descending order of importance. The overarching purpose of this format is to inform quickly and concisely, and there is a built-in understanding that the audience does not have to stay for the entire story to glean the main points.

Dramatic narrative, in contrast, is designed to engage the audience emotionally, which can motivate them to take a specific action. These stories tend to focus on an individual or small group with whom the audience can closely identify. The narrative usually follows the three-act structure (or what is commonly referred to as a beginning, middle and end), and the audience must follow the entire story to learn what happens and, most importantly, understand why this journey was worth their time and attention.

One of the most common problems I’ve observed over the years occurs when organizations confuse the kind of story they’re telling with the intended outcome. Simply put: If your goal is to spread awareness, the journalistic model is fine. But if you want your audience to actually do something – to sign, to march, to give – then you need dramatic narrative. Emotions are the precursors to actions, and journalistic storytelling simply isn’t designed to provoke emotional engagement.

Second, it’s time to move beyond the “broken person model” of storytelling. Also known as “deficit-based” framing, these stories introduce us to an individual at a crisis point (if not the lowest point) in their life. They are unhoused, unemployed, food insecure, a victim of domestic violence, addicted to drugs, or any combination of such dire circumstances. Through some means (often unspecified, which is another problem), they come into contact with our organization, and thanks to a specific program or initiative, they emerge a “fixed” person with a better life trajectory. (You can read more about problems caused by deficit framing in our March 2022 blog post.)

This storytelling model can evoke pity, but what you really want is empathy. Writing in Psychology Today in 2015, Dr. Neel Burton explained the key difference between pity and empathy: “Pity is a feeling of discomfort at the distress of one or more sentient beings and often has paternalistic or condescending overtones. Implicit in the notion of pity is that its object does not deserve its plight, and, moreover, is unable to prevent, reverse, or overturn it. Pity is less engaged than empathy, sympathy, or compassion, amounting to little more than a conscious acknowledgment of the plight of its object.”

The antidote to this common problem is, as you might guess, asset-based framing. Trabian Shorters, a thought-leader on this form of storytelling, calls it “a narrative model that defines people by their assets and aspirations before noting the challenges and deficits.” Or as we like to say at The Goodman Center, let your audience meet a person before they see a label. (Read more on asset-based framing in our March 2022 and May 2022 blog posts.)

Third, please stop calling everything a story. I cannot count the number of websites I’ve visited that present client testimonials but label them stories. There is no denying that testimonials have value – putting a human face on your proof of concept is always better than numbers alone. But a quote from a client thanking the organization for turning their life around rarely has the same impact as a full-fledged story in which we can see (and feel) for ourselves how that life was transformed. (The same can be said of most case studies, organizational histories, and donor profiles, which all have the potential to be powerful stories but are usually presented without the key elements.)

Fourth, even elite athletes have coaches and trainers, so…. If you want to enhance your storytelling skills and avoid the problems noted above, don’t be reluctant to ask for help, and I hope your first call will always be to The Goodman Center.

Our new Director, Kirsten Farrell, has storytelling in her DNA. As a member of the nationally recognized Impro Theatre, she is part of a company that crafts long-form improvisational plays, literally creating 90-minute stories on the fly in front of live audiences. You simply cannot do that unless you know the rules of storytelling inside and out (and also know how those rules can be bent or even occasionally broken and still delight an audience.)

As an advisory team member for The Corporation for Supportive Housing’s “Speak Up! Program LA,” Kirsten trains people with lived experience of homelessness to tell their stories. And since joining The Goodman Center in 2021, she has facilitated dozens of in-person and online workshops helping public interest organizations across the U.S. and around the globe hone their storytelling skills. I am honored and thrilled that she will be continuing the work I started back when I was filling up my car’s tank for $10 and making calls on my very cool Nokia flip-phone.

Fifth and last, never lose faith in the power of your stories. They are, always have been, and always will be the essential currency of human communication. Which is why I will end my last newsletter with the same words we use to end every storytelling class we offer:

Numbers numb, jargon jars, and nobody ever marched on Washington because of a pie chart. Stories, by their very nature, tend to get stored in our brains. So, if you can change the story inside someone’s head, you’ve taken the first step to changing the world.