When considering ethical storytelling, experts often focus on how we gather stories, acquire deep consent, and use asset-framing and asset-based language. These are excellent practices, but Jess Crombie, senior researcher and lecturer on Documentary Storytelling and Ethics at the University of the Arts London, wants us to go one step further. She wants the power to shape narratives to belong to the people who are affected by the issues we are trying to solve, and that means deciding the way their stories are obtained, developed, and told.

When considering ethical storytelling, experts often focus on how we gather stories, acquire deep consent, and use asset-framing and asset-based language. These are excellent practices, but Jess Crombie, senior researcher and lecturer on Documentary Storytelling and Ethics at the University of the Arts London, wants us to go one step further. She wants the power to shape narratives to belong to the people who are affected by the issues we are trying to solve, and that means deciding the way their stories are obtained, developed, and told.

In her report, “Rethink, Reframe, Redefine,” the sharing decision-making throughout the storytelling process is tested with a group of Rohingya storytellers who are living in Bangladesh as refugees.

Rohingya people are a Muslim ethnic minority group who have been denied basic rights, citizenship, and protection by authorities in Myanmar. They are the world’s largest stateless population and are living in over-crowded camps in Bangladesh.

Jess Crombie at work

Combie’s report is phase one of a study started in 2023, in which Rohingya storytellers teamed up with Crombie, staff

from the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR), and translators to create fundraising appeal materials to raise money for UNHCR’s work in Cox’s Bazar, a Rohingya refugee camp. These materials included a direct mailer, information insert, designed envelope, and emails sent to existing donors.

Their quest was to discover whether the process of co-producing these materials and being led by people with lived expertise could be sustained and scaled into day-to-day use.

It is an incredible report. I encourage you to read it for yourself, but here are some of my biggest takeaways (please note I had to take two passes at the report, because during the first pass I highlighted EVERYTHING.)

Take-Away 1:

Storytelling can be generative instead of extractive

I admit it, I have used a lot of “mining” language to talk about stories. I’ve described them as gold, an invaluable resource, something we have to collect and dig for. On its own, recognizing the beauty and value of stories is a great thing. It is when we go for them like strip-miners that we create harm.

When, instead, we partner with the people we serve, the storytelling process can be an investment in relationships and skill-building for all involved. The first time I saw this process in action was when I participated in the Speak Up program at the Corporation for Supportive Housing.

In this eight-month program, storytellers, coaches, and trainers learned together, built together, and ultimately the power to make decisions about the stories and how they were used were in the hands of the storytellers. Ann English, who was the program director for 10 years, says that our job is to be “an architect of creating space,” and continue to ask ourselves, “how do we put back into the [storyteller]?”

Take-Away 2:

A “donor-led” model can lead to perpetuating harmful narratives

When decision-making about our content is determined solely by metrics on donor response, then our messages tend to stay within strict parameters of their comfort zone. This is possibly why deficit-framing has had such staying power.

Instead, we could create a donor-leading model which builds solidarity between the affected community and the donors. Our narratives could lead our dedicated supporters away from the lure of savior-mentality and towards true partnership.

Take-Away 3:

Voice is Power

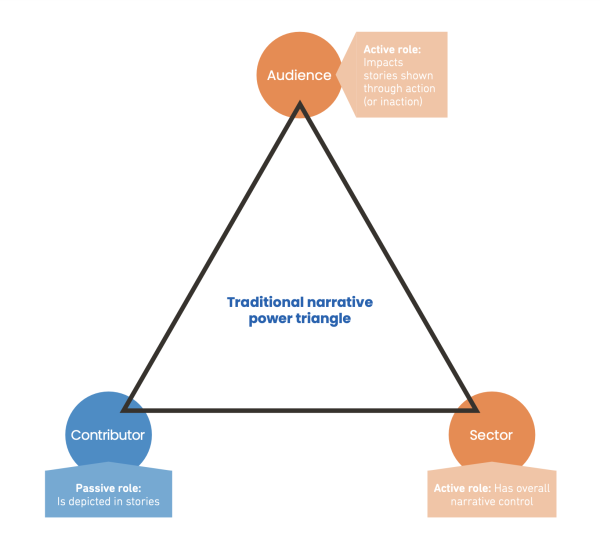

Gathering and retelling someone else’s story is very powerful, but much of that process (what questions are asked, what pictures are taken, how the story is edited) is out of the control of the true owner of the story. “It is more than just having your quotes or images included in storytelling, it is about the power to make decisions about all aspects of the narrative.” (Crombie, 2024, p. 13)

Crombie’s report shows how that power can be acknowledged and shared. Decisions about every aspect of producing the donor appeals were made by the whole team. They also set aside time to speak frankly about the status and power dynamics between staff and the storytellers who depended on aid from UNHCR.

Take-Away 4:

We are still figuring this out… together.

Rethink Reframe Redefine shares their methodology, what worked, what didn’t, and how they will do things differently next time. They share some essentials for this kind of work (i.e. trauma-informed facilitation) and mistakes they learned from (i.e. careful vetting, keeping the ratio of participants even, and removing parts of the process that felt competitive.)

There is a lot to learn from and build upon in this report. The next installment should be coming out in the next few months. I, for one, will spend that lag time reading more of Crombie’s work: The People in the Pictures and Who Owns the Story?