In Case You Missed It: This month’s ICYMI (from the October 2004 issue of Free-range Thinking) asks the question… when it’s your turn to present is the audience seeing the real you? In an interview with the late Eda Roth, Andy Goodman uncovers the secret to playing yourself.

Meryl Streep, as Nora Ephron, with Jack Nicholson in Heartburn.

In the movie “Heartburn,” Meryl Streep played a character based on novelist and screenwriter Nora Ephron, so when the American Film Institute honored Streep earlier this year, Ephron was among the luminaries invited to speak. Never one to miss an opportunity for a trenchant observation or two, Ephron had this to say about watching America’s finest living actress portray, of all people, her: “It’s a little depressing knowing that if you audition [to play] yourself, Meryl will beat you out for it.”

I was reminded of Ephron’s comment when I sat down recently to interview Eda Roth, a communications consultant who helps clients become more effective presenters. Whether coaching business executives from AT&T, Levi Strauss, or Coca-Cola; or public interest professionals from the California Health Care Foundation, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Executive Nurse Fellows Program, or UCLA Medical School, Roth says she usually encounters the same three problems. And first among them is the surprising difficulty most people have simply playing themselves.

Eda Roth

Although she began her professional life as a social worker, Roth caught the acting bug early on, got her masters of fine arts in acting at New York University, and undertook the arduous task of finding work. The jobs that came her way most easily were more in the line of teaching than acting, and in 1985 Roth joined the faculty of Boston University to teach voice, speech and dialect in the theater program. Since then she has coached such Hollywood notables as Holly Hunter, Richard Dreyfuss and Jeff Bridges, taught graduate-level courses in leadership and “executive presence,” and built a business as a communications consultant for commercial and nonprofit clients.

The 3 Most Common Problems

While her customers run the gamut from hard-charging corporate types to soft spoken policy wonks, Roth says she sees a common set of problems when it comes to presenting. “Most people are very constricted by either their own or a societal sense of professionalism,” she says. “The same people who are very expressive at their children’s soccer games are not as expressive in their professional lives.” Simply put, the number one problem Roth encounters comes down to two words: “Being yourself.”

To free those clients who are bound by this psychological straightjacket, Roth conducts an exercise in which presenters must start their talk by literally running into the room and exclaiming, “I have the most incredible thing to tell you!” Most clients will respond by jogging to the podium with an embarrassed look on their faces, but Roth sends them back and demands a full-out sprint. “I want to break through the constrictions of so-called professionalism and get them to open up to the possibility of a bigger and more visceral expression,” she explains.

Much to her clients’ relief, Roth doesn’t expect them to incorporate the running start into their actual presentations. “It’s a matter of stretching out a lot so that when the personality snaps back, it’s a little larger than it was,” she says. In a similar exercise, Roth will ask presenters to identify the emotion—excitement, anger, empathy, frustration—that is central to their talk. Once they have it, she instructs them to make their points saying exactly what they mean shorn of any euphemisms or diplomatic language. This helps presenters feel the emotion more clearly, and that’s what Roth wants them to remember when they eventually put the diplomatic language back in.

“The second major problem,” says Roth, “is connecting with the other people in the room—conveying why the topic is important to you and why it should be important to them as well.” To address this problem, Roth asks presenters to deliver their talk as normally prepared, but to insert the line, “I love you,” into every paragraph. Again, clients usually take to this exercise like a lobster to boiling water. “They resist it,”

she says with a laugh, “but this is a behavioral exercise,” she continues, stressing the word “exercise,” and Roth maintains it helps presenters focus on their connection to the people in the room.

Roth has a one-word summary for the third most common problem: size. “Most people, when they are in a room, literally do not see the room they are in. They do not fill the space,” Roth says. “Their awareness expands about three inches beyond their own bodies.” To tackle his problem, she asks presenters to imagine themselves addressing a single person across a very large room. “Even if you have a microphone,” she explains, “if you don’t speak up, there’s no evidence of your enthusiasm and passion for what you’re saying.”

Learning from Dr. King

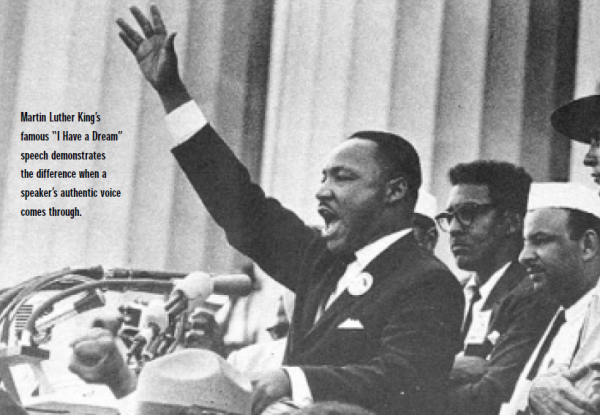

As part of her coaching, Roth has presenters watch a videotape of Martin Luther King’s legendary “I Have a Dream” speech, but not simply for inspiration as some might guess. What’s striking about the speech, Roth points out, is how Dr. King’s demeanor changes when he moves into its most famous passage. Before he talks about his dream, King is, as always, an effective orator. “But when he goes into the dream section,” says Roth, “he’s off the page. He’s in ministerial mode, and that is when he’s most deeply connected to who he is.”

As part of her coaching, Roth has presenters watch a videotape of Martin Luther King’s legendary “I Have a Dream” speech, but not simply for inspiration as some might guess. What’s striking about the speech, Roth points out, is how Dr. King’s demeanor changes when he moves into its most famous passage. Before he talks about his dream, King is, as always, an effective orator. “But when he goes into the dream section,” says Roth, “he’s off the page. He’s in ministerial mode, and that is when he’s most deeply connected to who he is.”

Having watched that tape in one of Roth’s workshops, I can confirm that the difference is noticeable, as is the effect the lesson has on her students. The more of themselves they reveal in subsequent exercises, the better their talks become. “I highly recommend having Meryl Streep play you,” Nora Ephron joked at the AFI dinner. As that isn’t a very likely option for most of us, it’s probably best to follow Roth’s advice and get better at playing yourself. The audience at your next presentation will be glad you did. And so will you.