In Case You Missed It: This month’s ICYMI is written by Andy Goodman in August 2017 where he answers some of – what were and still are! – our most frequently asked questions.

What is the ideal length for a story? Is it okay to make up stuff? How can I use social media to tell stories? These are just some of the questions we regularly hear when we conduct storytelling workshops for our clients. And after leading over 500 workshops for organizations large and small around the world, I usually have a pretty good idea of what’s coming every time we pause for Q&A. So this month we’d like to share our answers to the ten most frequently asked questions, because we’re guessing that you may have been wondering about some of these things, too.

Q. What is the ideal length for a story?

A. Let me state definitively and without fear of contradiction: it depends. If you’re a great storyteller, you can take several minutes. If you’re boring, even thirty seconds will feel too long. That said, consider what happens when someone says, “Hey, I’ve got a story for you.” You’re all ears, right? But whether you’re aware of it or not, a little clock starts in the back of your head, and somewhere around two or three minutes the alarm goes off and that story had better be over. I’m not sure why – maybe that’s because most stories on the news are a couple of minutes long, or that’s how long commercial breaks are on TV – but whatever the reason, most listeners will usually give you 2-3 minutes. (For more on this subject, check out “The Ideal Length of Everything Online, From Tweets to YouTube Videos,” Adweek, 10/24/14. Two stats of particular note: the average length of the top fifty YouTube Videos that year was 2 minutes and 54 seconds; the average length for blog posts was 1,600 words.)

A. Let me state definitively and without fear of contradiction: it depends. If you’re a great storyteller, you can take several minutes. If you’re boring, even thirty seconds will feel too long. That said, consider what happens when someone says, “Hey, I’ve got a story for you.” You’re all ears, right? But whether you’re aware of it or not, a little clock starts in the back of your head, and somewhere around two or three minutes the alarm goes off and that story had better be over. I’m not sure why – maybe that’s because most stories on the news are a couple of minutes long, or that’s how long commercial breaks are on TV – but whatever the reason, most listeners will usually give you 2-3 minutes. (For more on this subject, check out “The Ideal Length of Everything Online, From Tweets to YouTube Videos,” Adweek, 10/24/14. Two stats of particular note: the average length of the top fifty YouTube Videos that year was 2 minutes and 54 seconds; the average length for blog posts was 1,600 words.)

Q. If everyone is telling stories, won’t my audience get tired of stories?

A. After a ten thousand year run, it’s doubtful that stories have suddenly lost their power. The reason stories fail is not that people are tired of stories in general, it’s more that the storyteller has failed to produce something fresh, authentic and compelling. Romantic comedies are a case in point: we’ve all seen a bunch of them, and everyone knows what to expect, but when someone finds a fresh way to tell the story, we’ll stand in line to see it. (Still not convinced? Go see “The Big Sick.”) When people suddenly stop going to movies, watching TV and reading books, then you can start worrying.

Q. I feel uncomfortable telling somebody else’s story – I feel like I’m exploiting them. Do you have any advice about this?

A. We hear this a lot, and we’re very sensitive to the issue of exploitation or appropriation of someone else’s story. The best-case scenario is when the individual can tell her or his own story – nothing is more powerful than first-person storytelling, i.e., having someone stand before an audience and say, “This happened to me.” If your storyteller is not comfortable or simply cannot be in a certain place at a certain time, then the next option is to obtain their permission (preferably in writing) to tell their story, using their name and all the facts as they happened. Sometimes people will want you to tell their story but will ask you to change their name and a few details to protect their identities – that’s a third option. And lastly, in some cases, you may have a community that’s so small, changing the name and a few details would not be enough to hide their identity. In those cases, you can create composite characters, saying something like, “This is the story of Mary. Everything that happens to Mary happens to women in our program, and all the outcomes are real outcomes. But Mary actually represent many women, so while her story isn’t factual, it is truthful nonetheless.”

2024 Update: In our storytelling workshops we direct people towards the resources found at EthicalStorytelling.com. They have an excellent media consent form that you can download straight from their website.

Q. Is it okay to make some things up? (Or: How much can we embellish?)

A. If you can tell a story exactly as it happened, being faithful to every single fact, that’s the best-case scenario. Sometimes, however, you may be fuzzy on some of the facts or may not be able to recall certain details, such as specific quotes from a conversation. In that case, if you offer your best recollection, that’s acceptable as long as (a) you disclose to your audience that some parts of the story are “best recollections,” and (b) you are not in any way altering the basic truth of the story. For example, if you say that you met someone on a Tuesday and it turned out to be a Thursday, it’s unlikely that would have a material effect on the truth of the story. But if you say you personally saw thousands of homeless individuals when, in fact, there were only hundreds, then you are stretching the truth in what is probably a misleading way.

Q. What’s the best way to tell/share our stories? (Or: How can I use social media to tell our stories?)

A. Your website is probably your primary audience-facing medium, so that’s the first place to consider. And if you want to tell stories on your website, video is your best friend. Your audience is much more likely to sit and watch a 2-3 minute video than they are to read 750-1000 words. If video is too expensive or takes too long to produce, you can also tell stories on your website using pictures with captions or short summaries. (Exposure.co or Atavist.com are great resources to help you craft image-driven stories.) Newsletters – either electronic or hard copy – are also great vehicles for storytelling, and if you’re delivering speeches or making presentations, you should weave stories in there as well. As for social media, you can certainly tell stories on YouTube and Facebook, but I see the principal value in Twitter, Instagram and similar tools as pointers more than carriers of content. Tweets can serve as compelling headlines that make you follow a link to a place where you can spend a little more time watching or reading a story.

Q. Is there a correct amount of data to sprinkle into your story?

A. I have yet to see research that specifies a certain number of data points per words in your story, but I’m a believer in “less is more.” If your 2-3 minute story can make one data point memorable and compelling, that’s enough.

Q. What if I don’t have enough time or space to tell a complete story?

A. First, if time or space is limited, consider “connecting narrative moments.” This term, coined by Frank Dickerson, is a fancy way of saying that sometimes a snippet from a story will do – a single moment or a scene that evokes emotion without having to tell you the entire story. (Ernest Hemingway is famously credited with evoking an entire story with only six words: “For sale. Baby shoes. Never worn.”) But you should also consider creating a little extra space or time for a story even where you think there isn’t any permitted. I know of several instances where people had to submit proposals or make presentations that had very strict guidelines and there was no room for a story. They filled in all the boxes as required, gave all the information necessary, but then added a short story to bring a human dimension to all that information. I believe it’s worth the risk.

Q. What if you’re talking to an audience that actually prefers data to stories?

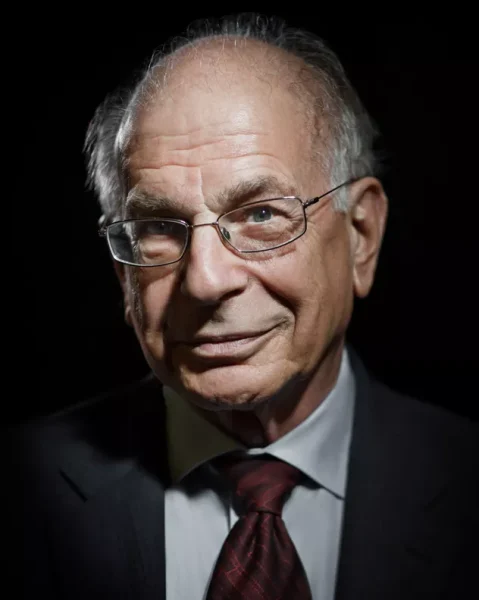

Daniel Kahneman

A. You may run into audiences – scientists, economists, researchers – who are inclined to see data as serious business and stories as “fluff.” I’m not insisting that you force-feed them stories – sometimes, if data is what they want, just give them the data! But if those same people are ever in the business of changing how people think and behave, then you have to explain to them that numbers do not have that power by themselves. (If you want to cite a higher authority than me, refer them to the Nobel Prize winning economist Daniel Kahneman, who said, “No one ever made a decision because of a number. You have to give them a story.”) Stories are like the software of the mind, telling us what data to let in, and what data to ignore. If you change the story, you can open their minds to your data, so you need to tell stories first.

Q. You say that audiences can only identify with one person – but what if the story is really about a team that worked together towards the goal. How do I tell that kind of story?

A. Identification is a one-on-one process, that’s true. People do not naturally identify with teams, groups, or an entire organization. That said, if your story is about a team, then introduce the members of the team one by one, and let your audience meet them as individuals. The audience can then track the progress of the story as the responsibility for moving the action forward passes from one team member to another.

Q. I work in policy (or systems) change. I don’t do direct service delivery. How can I tell a compelling story?

A. You have two options. The best-case scenario is to tell a story that shows at ground level (and featuring real people) how your policy or systems change is improving lives. If your audience can see that change up close and get a true feeling for the impact it’s having, then they will follow the links in the chain that ultimately lead from ground level all the way to your offices. If you simply don’t have access to those stories, you have another option. Effecting policy or systems change often boils down to getting people together in a room and moving them from no to yes. Changing minds isn’t easy – it’s a challenge we all face in one way or another – so stories about how that is accomplished hold interest for everyone and are also worth telling.